Worth and work: gender, occupation and the economics of inequality

24 Apr 2025

Meghna Sharma, Research Fellow

This blog was originally published in March 2025 on the website of Adzuna, one of the largest online job search engines in the UK.

More than a century after the first International Women’s Day in 1911, we’re still debating the gender pay gap—and for good reason. Since the Equal Pay Act of 1970, which prohibits the unequal treatment of men and women in terms of pay and working conditions, the UK introduced various measures to address gender inequality in the workplace. One such measure was introduced in 2017, where companies with more than 250 employees were mandated to report gender pay gap figures on an annual basis. Despite various efforts, the gender pay gap for full time employees stood at 8.3% in April 2022, according to the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), 2022. This gap widens as we factor in part-time employees, reflecting the interplay between occupational segregation, work-life balance, and historical undervaluation of women even in women-dominated sectors.

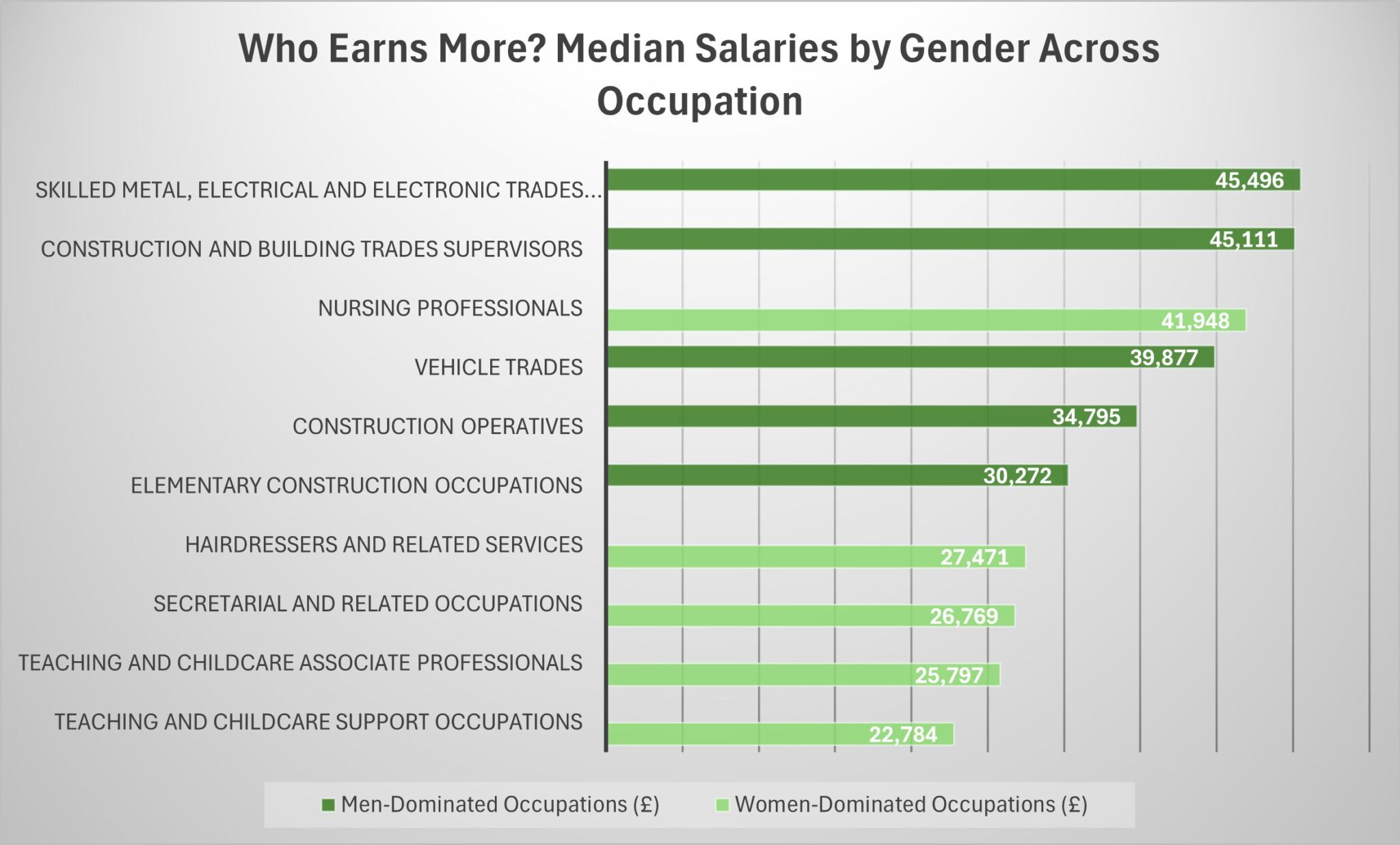

To understand this, we examined the distribution of labour force in full time employment by gender for SOC minor (2020) occupations from October 2024 to December 2024. We identified the most women-dominated as well as men-dominated occupations based on the difference in proportion of full-time employees by gender. Teaching and Childcare Associate Professionals, Secretarial and Related Occupations, Hairdresser and Related Services, and Nursing Professionals stand out as women-dominated occupations, each with at least 90% labour force to be women. Annual Median salary for these professions from October 2024 to December 2024 on average was £28,954. Teaching and Support Occupations had the lowest median salary (£22,784), despite a high demand for labour; 95,573 professionals in demand according to Adzuna. This is followed by Secretarial and Related Occupations with a median salary of £26,769 and Hairdressers and Related services with £27,471 per annum.

Nursing professionals stand as a notable exception among women-dominated occupations, commanding a significantly higher median salary (£41,948) compared to other women-dominated sectors. So why is nursing different? A few key factors set it apart: Agenda for Change NHS pay structure that standardised health workers’ salaries, union representation through the organisations such as Royal College of Nursing, and the training and educational requirements for the jobs. As noted in the King’s Fund report, “Closing the Gap,” nursing has benefited from focused governmental wage policies and career progression frameworks that many other care-oriented professions lack.

The women dominated occupations share some commonalities contributing both to gender composition and pay structure. First, they predominantly revolve around care work that also requires emotional labour such as through teaching, nurturing, supporting, and personal services that have been traditionally associated as women roles. These occupations require significant emotional and personal management skills that are economically undervalued despite their need and complexity. Secondly, most of these occupations follow fragmented employment structures, while nursing falls under NHS, services like childcare, teaching support, hairdressing are dispersed across smaller establishments, self-employment, limiting their collective bargain. Although collective bargaining is influenced by multiple factors beyond employment structure, the fact that these sectors are women-dominated speaks for itself. Moreover, women in these sectors face additional disadvantages when their gender intersects with other factors such as race, disability, or socioeconomic background, creating multiple layers of wage penalties that compound existing gender disparities.

In contrast, men dominance stands out in Construction Operatives, Elementary Construction, Construction and Building Trades, followed by Skilled Metal, Electrical and Electronic Trades Supervisors, Vehicles Trades and Electrical and Electronic Trades roles with at least 94% employees to be men. Among these roles, median salary was notably high: £45,495 for Skilled Metal, Electrical, and Electronics Trade, and £45,111 for Construction and Building Trades roles. These men-dominated occupations exhibit a structure that correlates strongly with skill specialisation, and supervisory responsibility, unlike the emotional and personal skills required in women-dominated roles.

Despite being overwhelmingly men-dominated (99.54%), Elementary Construction Occupations have the lowest median salary (£30,272) among these roles. As documented in a research on the UK construction industry, these positions often serve as entry points for migrant workers and those with fewer qualifications, creating vulnerability to wage suppression. This internal stratification highlights that while men-dominated industries generally offer higher wages than women-dominated ones, significant wage disparities exist within them, disadvantaging lower-skilled workers despite the male majority.

These trends highlight the function of intersectionality in the gender pay gap—how the complex interplay between gender, migration status, education, and stereotypes leads to systematic undervaluation of workers across industries. Women in nursing, teaching support, and secretarial roles experience compounded pay-penalties when they also belong to ethnic minorities, with the pay penalty intensifying at these intersections. Similarly, men in elementary construction occupations experience wage suppression (£30,272) influenced by immigration status and educational qualifications, despite working in generally higher-paid men-dominated sectors. Trade unions have played a significant role in the dynamics, with strongly unionised sectors like nursing achieving better compensation structures (£41,948) through collective bargaining, while fragmented representation in hairdressing (£27,471) and childcare (£22,784) contributes to persistent low wages. The devaluation of skills deemed “feminine” in teaching and care work reflects deeply embedded cultural biases that transcend simple supply-demand economics, even when demand figures are high (95,573 for teaching support). Addressing these disparities requires policy interventions that recognise these intersectional factors rather than treating gender in isolation.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.