Is a remote and flexible job the new labour high class?

17 Feb 2025

Helena Saenz de Juano Ribes, Research Economist (Fellow)

Helena Saenz de Juano Ribes, Research Economist (Fellow)

This blog was originally published in January 2025 on the website of Adzuna, one of the largest online job search engines in the UK.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 marked a significant turning point for remote work globally and particularly in the UK. Practically overnight, millions of workers transitioned from office-based jobs to working from home. Companies had no other choice but to adapt rapidly, investing in technologies to facilitate remote operations, such as virtual meeting platforms and collaborative tools.

This shift demonstrated the potential benefits of remote work, including reduced commuting times, enhanced work-life balance for employees, and expanded employment opportunities for individuals living in remote areas, or those with disabilities. According to the Office of National Statistics (ONS), the number of people working from home in the UK more than doubled between October to December 2019 and January to March 2022, increasing from 4.7 million to 9.9 million.

Using Adzuna’s intelligence portal vacancy data we observe the demand for on-site jobs plummeted during the height of the pandemic when economic activity slowed dramatically. Post-2020, remote jobs increased substantially, seeking to replace many non-essential on-site roles. However, as restrictions eased and workplaces reopened, a shift toward hybrid work emerged. By 2021, many businesses pivoted from fully remote setups to hybrid models, requiring employees to commute to the office two or three times a week. This transition addressed some of the challenges associated with full-time remote work, such as feelings of isolation, reduced opportunities for collaboration, and concerns about career visibility.

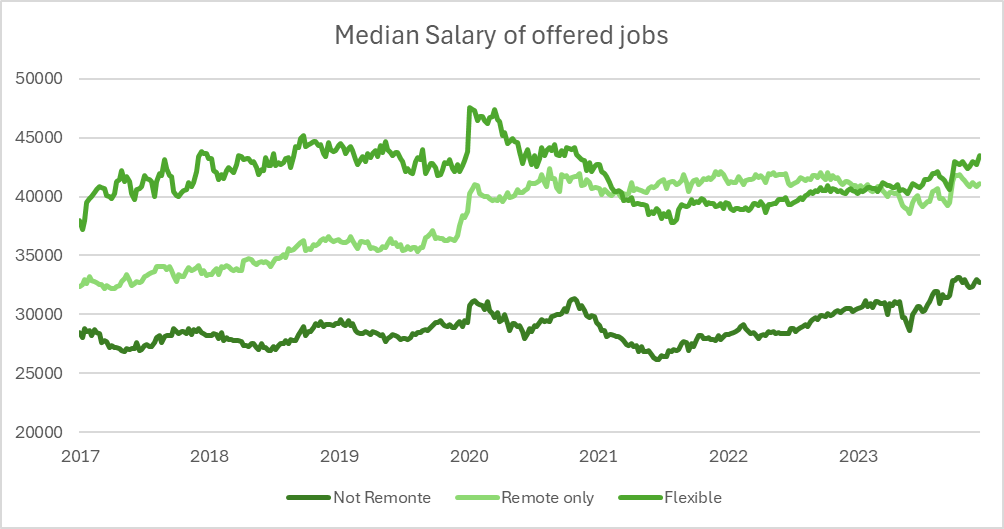

However, the shift toward remote or flexible work accentuated existing inequalities in compensation compared to traditional on-site jobs. As illustrated below, offered median salaries show a clear disparity across these work models. Remote and hybrid roles consistently command higher pay.

This disparity can be explained by several factors. Even before the pandemic, remote and hybrid roles have been predominantly found in high-paying sectors such as technology, finance or consultancy. These industries demand specialised skills and expertise, which employers usually reward with competitive salaries. Conversely, on-site jobs are more common in lower paying sectors like retail, hospitality and manual labour, where wage growth is typically slower.

Additionally, remote and hybrid work often incorporates flexibility as part of their compensation package, which increases their appeal. This “flexibility premium” has become a critical factor for attracting and retaining talent. On-site roles typically lack the autonomy to adjust their schedules, which limits their ability to manage personal and professional responsibilities effectively. Moreover, commuting, often long and costly, has been shown to negatively impact well-being.

Despite all of this, many on-site jobs proved to be essential during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Workers in healthcare, logistics, and essential retail ensured societal functions continued amid the crisis, often at a great personal risk. However, as the median salaried depicts, this critical contribution was not matched by structural improvements in salaries, or job quality.

Policy solutions are necessary to address these inequities. There is a new trend among large-company employers to force the discontinuation of remote work as it was before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, many other employers recognise that the flexible model has emerged as a dominant legacy of the pandemic, balancing the flexibility of remote work with the collaborative benefits of in-person interactions. As of this autumn 2024, ONS data shows that 13% of the UK workforce remains fully remote, while hybrid workers now constitute 28%. Therefore, for those whose jobs are forcibly on-site, governments and employers should explore measures such as enhanced wage support, subsidised commuting costs, and investment in workplace well-being programmes to compensate the rigid schedules and lengthy commutes.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.