Labour Market Statistics, February 2025

18 Feb 2025

Seemanti Ghosh, Principal Research Fellow (Economist)

Seemanti Ghosh, Principal Research Fellow (Economist)

This briefing sets out analysis of the Labour Market Statistics published this morning. Today’s LFS data covers the period from October to December 2024. While we discuss the numbers released today, we also briefly reflect on historical data and share our thoughts about the future.

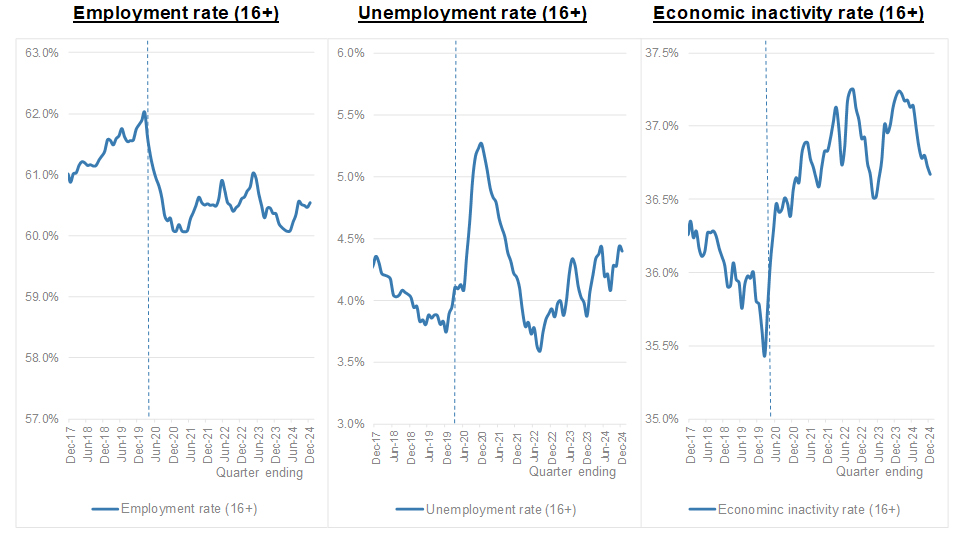

The figures out today show stabilisation of employment, unemployment and inactivity rates. The UK employment rate for people above 16 years was estimated at 60.5% in Oct-Dec 2024. This is above estimates of a year ago, and the same as the last quarter. The unemployment rate for people above 16 years was estimated at 4.4%, which is again higher than a year ago (3.9% for Oct-Dec 2023) but the same as the last quarter. Economic inactivity for people above 16 years was estimated at 36.7%, which is lower than a year ago (37.2% for Oct-Dec 2023) but the same as last quarter. However, all indicators remain worse than they were before the pandemic.

Figure 1: Employment, unemployment and economic inactivity rates (%)

Source: Labour Force Survey. Vertical dotted line indicates start of first Covid-19 lockdown.

Vacancies continue to decrease. Today’s labour market data shows that the estimated number of vacancies was 819,000 in the UK in November 2024 to January 2025, which is a decrease of 9000 or 1.1% from Aug-Oct 2024. The sector that has seen the highest fall in this period is service based sectors (24,000), followed by wholesale and retail (8000). Total estimated vacancies were down by 110,000 (11.8%) in November 2024 to January 2025 from the level of a year ago. In November 2024, the Labour government announced its ambition to achieve an 80% employment rate in the UK which would involve moving around 2.2 million more people into work. However, the question that looms large is ‘will there be enough jobs?’ Concurrently, payroll employees have decreased by 19,529 since Aug-Oct 2024.

The 2024 Autumn Budget announced the changes in employer National Insurance contributions (NICs) and the National Living Wage (NLW) due to affect employers from April 2025 and this has had a notable impact on business confidence due to the perceived increase in the financial burden on employers. With the labour market predicted to worsen over coming months, we analysed historical data to understand how different sectors have responded in the past to National Insurance changes in the UK (2022, 2011, 2003) during the pre- and post-implementation periods.

Labour intensive sectors such as wholesale, retail, construction, transport and storage, hospitality and other service-based sectors have reduced both headcounts and vacancies either in anticipation or immediately after the change was effective. These sectors are most at risk since they have higher entry level jobs and therefore pose a threat to young people’s traditional routes of entry to the labour market. Whereas businesses in sectors that employ a higher proportion of skilled workers such as professional, scientific and technical activities, finance and insurance and information and communication, adjusted headcounts with a lag of a quarter or two. Therefore, any effect on these sectors (if any) can be expected to be seen in the second half of 2025.

Figure 2: Vacancies and payroll employees by sector pre-post 2022 NI change

Pay growth is accelerating, overall up by 6%, up by 6.1% in private and 5.7% in public sectors. Both regular pay (excluding bonuses and arrears) and real pay appear to be rising. This is well below the heady peaks of 8% growth that we saw a year and a half ago, but as the ONS note, those figures were aided by large public sector pay settlements.

The 2024 Autumn Budget that announced an increase in both employer NICs and the NLW has had a notable impact on business sector confidence, due to the perceived increase in the financial burden on employers. Various surveys have indicated that a significant number of employers are considering workforce reductions in response to the upcoming changes over next few months, which means we could expect to see a rise in redundancies.

Employers are also expected to respond by increasing prices which could lead to inflationary effects as highlighted by the Bank of England, by scaling down investment which would deter growth, and via an attempt to raise productivity which would mean longer work hours for existing employees (see views from employers published by CIPD yesterday). The UK government justified the increase in employer NICs to invest in public services, which may ease labour market challenges in the long run. But in the short term, the government needs to build business confidence in the upcoming budget and the finalisation of Labour’s industrial strategy has never felt so urgent.

To encourage business investment and sustain economic stability, the government could incentivise investments in technology to boost productivity and efficiency and offer targeted support to industries most affected by rising costs. A balanced approach that combines short-term business support with long-term public service investment will be crucial in navigating the economic challenges ahead.

Any views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Institute as a whole.